![]()

May 25, 2016 | by Ethan (email) |

If you’re a regular reader, you know this detailed guide is the culmination of many days shadowing expert general contractor and carpenter Steve Wartman. I was on-site as he and his crew built this deck, taking pictures of the progress, documenting the work and discovering tips and tricks. I’m convinced that there’s no better way to learn how to tackle home improvement projects than following a licensed contractor through a build. If you enjoy this article, check out our other Project Guides. To stay current on all our Pro-Follows, subscribe via RSS or email.

If you live in the greater Baltimore area and are considering adding a deck to your home (or any other sort of home improvements), I suggest you give Steve a call. This article is a great example of the high quality and professionalism that Steve and his crew bring to every job. For more examples, check out our articles on building a shed or how to hang drywall.

The same homeowners that had Steve’s crew build a custom shed have contracted him again to construct a new, composite deck on the back of their home. They went with Trex brand composite materials for the build, because Trex is virtually maintenance free, meaning the homeowners won’t ever need to seal, brighten or strip the decking boards.

Here’s Steve to give you a short introduction to this project.

Video Summary: Steve describes a plan to build a new, 12 x 24′ deck and a 4′ set of stairs. It’ll have two rows of buried posts, Trex composite decking, Trex trim boards and a white vinyl rail system.

Determining the location of the deck was easy. It was more difficult to determine how many footers were required and where they were going to be located. This video shares some details about footer and ledger board requirements.

Video Summary: How the deck attaches to the house is one of the factors that determines the required number of deck posts and footers. Other considerations include the size and shape of your deck, how much weight it will hold, and the size of the beams. This deck is rectangular in shape, and the homeowners aren’t planning on adding a hot tub (or other heavy objects). Since Steve’s crew couldn’t through-bolt the ledger board, they’ve installed two rows of posts, creating a “free-standing deck.”

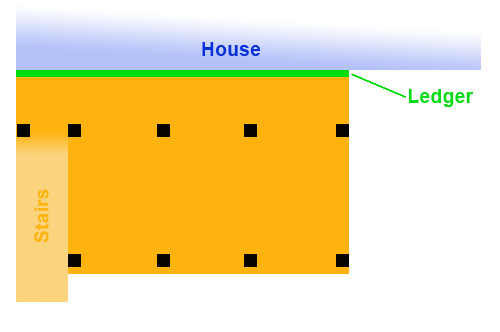

The first row of posts was placed 3′ off the house, and the second row of posts was 8′ after that. Posts are spaced no more than 8′ apart so that means we have four posts per row, with the first row having 1 additional post to account for the stairs. Here’s a sketch of the deck and posts.

After Steve determined the footer locations, the crew ran several string guides and started digging. This was no small task because they decided to cut through the brick patio and underlying concrete before learning it was 5-1/2″ thick.

Each footer needed to be deeper than the frost line, and here in Maryland that means footers must be at least 30″ deep. In areas such as northern Minnesota, footers need to be at least 60″ deep, so check the code for your area before digging. Steve’s crew dug each hole about 24″ across. Before continuing, all the footers needed to pass inspection. In this jurisdiction, this was the only required interim inspection, and the checklist includes:

Pro-Tip: Before you start digging, have underground lines (water, gas, power, communication, etc.) located. Call the North America One Call Referral Service (1-888-258-0808). It’s free and required by law.

The inspection went smoothly, and Steve’s crew started pouring the footers. Using 80lb. bags, they mixed enough concrete to achieve an 8″ thick pad.

They used a garden hoe to make sure the concrete would set with a nice, flat surface.

While the concrete cured, the guys started on the ledger board. They installed a 2 x 10′ ledger along the entire length of the deck, taking care to ensure it was completely level. Steve and his crew temporarily secured it in place using a powder charge nailer. Here’s a quick demonstration:

Video Summary: In the video, Steve shares how driving temporary anchors makes it easier to install the ledger board. For this brick and masonry house, you have to use concrete fasteners, and a powder charge gun actually uses a .22 caliber shot to quickly drive the anchor. It’s important to pre-drill a hole so you don’t split the board which also enables the nail to go further. That’s how they temporarily set their ledger board.

Next, the crew marked the locations of their joists. Often you’ll see joists spaced at 24″ on center (oc); however, with composite decking, joists need to be closer together. Steve’s crew marked their joists at 12″ oc. Predetermining the joist locations ensured that none of the concrete anchors will create an obstruction, and it allowed them to place an anchor in every bay (between each joist).

The crew used concrete anchors called Red Heads to secure the ledger board.

The concrete anchors needed to be staggered and, for the upper row, driven into the mortar between bricks. For each Red Head, the guys pre-drilled a hole, used a hammer to drive them in place, and a socket wrench to tighten them down.

The crew used pressure treated 6 x 6″ for posts on this deck. These were rated for “ground contact”, which, as you might expect, means they can be buried directly in the ground.

Pro-Tip: Pressure-treated lumber is infused with chemical and rated by the amount per cubic foot of wood. Ground-contact lumber has .40 pounds of preservative per cubic foot, and above-ground rated lumber has .25 pounds.

Pro-Tip: The size of posts required for a deck installation depends on the span being supported by the post, as well as the height of the deck. Steve’s crew prefers 6 x 6″ posts for their sturdiness; however, 4 x 4″s may be used in certain low-height installations. In certain very tall installations, cross-members may be required between the posts for added support and to prevent racking.

The challenges with installing deck posts include keeping each post:

The crew moved the first post into place and marked a line indicating the very top of the post which was even with the support beam. The reference point on the ledger board was the bottom of the floor joists.

Using a circular saw, they cut the post to the proper height, based on the previous measurement.

Using a reciprocating saw, the crew cut a notch for the support beam so that the top of the post was flush with the support beam.

The support beams consisted of two, 2 x 10″ boards nailed (and later bolted) together, side-by-side in the notch.

Pro-Tip: You may see support beams where the deck post is sandwiched between two pieces of 2x material. The method we describe here is better, because when the two boards are touching, they act as a single unit. Furthermore, separating the 2x material requires additional blocking in between the joists to support bolting, and therefore, longer bolts.

With the post cut to the appropriate dimensions, the crew moved it into place, and secured it with temporary boards. This was a tedious activity that required several pairs of hands and repeated measurements, but it was extremely important for the finished product.

The crew repeated the process for the middle post, and, after it was in place, added one of the 2 x 10″s that will makeup the support beam. This allowed them to double-check level and distance from the house across the entire gap, and make adjustments as needed to each post.

Again, the level was aligned just like a floor joist so that the top of the floor joist sat flush with the top of the ledger.

This process continued for all five posts in the first row along the house. The middle post was where two support beams butted against each other. The transition was accomplished by equally dividing the space in the notch between the two beams.

In this picture, you can see all the temporary boards that kept the posts and support beam in place.

Once the crew was satisfied with the entire row, they back filled the dirt and tamped it down, taking care not to move the post. Any movement required additional measurements to ensure nothing moved out of square with the house or the other posts, and that the post was still at the proper height.

The second row of posts went in much the same fashion except for one thing. Since the crew had the ledger and first row finished, they added a few joists and ran a string guide to make it easier to setup the rest of the posts. It’s also important to note that they established a 3/8″ slope (over the entire width) to direct water away from the house.

Once the crew had set a few more posts, they ran a tape measure along the diagonals to check for square.

This picture shows a crew member adding that second 2 x 10″ to form the support beam.

These two beam components were later secured with staggered carriage bolts through the post.

Since the ledger was already marked, lining up the joists was not a difficult task.

Here you can see the crew once again made sure the joists were square to the ledger. The importance of re-checking square measurements cannot be overstated in a deck build. If components start out of square, it will be hard to make the deck look good at the end.

Pro-Tip: Joists should always be placed “crown up” in an installation. All joists must be oriented identically in this manner to ensure the deck won’t have waves between the joists. In our tutorial on How to Build a Shed, we provide a video on checking and marking dimension lumber to identify the crown.

The crew did break out a planer at one point because they found a few boards were thicker than the others.

Pro-Tip: Double-check board dimensions, because you may find some variation in your lumber package. Never assume that all joists are exactly the same dimensions. Purchasing extra lumber allows you to be more choosy and avoid using bark-cut or bowed boards.

Each joist was toe-nailed in place with four nails, and then a Simpson hanger tie was added.

It was fun to see the crew use this palm nailer for fastening the hanger ties. It made driving the 10 nails into the hanger very quick–much quicker than could be achieved with a regular hammer, which is an acceptable (albeit much slower) alternative.

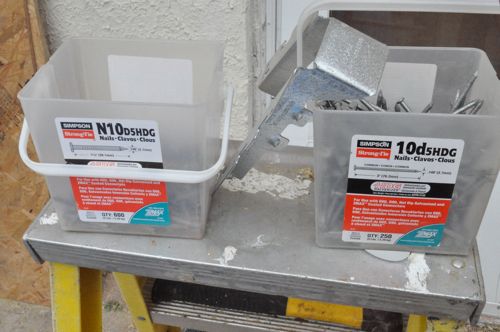

The guys used Simpson nails with the hanger ties. The shorter nails (N10) secured the hanger to the ledger, while the longer nails (10d) were used for the angled slots. Using the correct nails for hanger ties is very important, as the strength of the hanger is dependent on using the appropriate hardware.

As you may remember, the crew planned the joist spacing at 12″ oc since they were installing a manufactured composite decking surface. For traditional 5/4 pressure treated wood surface deck, 16″ oc is more common. Joist spacing depends on both surface material as well as spanning distance between the posts.

Pro-Talk: The term “5/4 lumber” is shorthand for lumber that is nominally 1.25″ thick (or 5/4s of an inch). 5/4 lumber is actually finished to 1-1/16″. The type of 5/4 lumber used on decks has rounded edges and is known as “decking board”. Composite decking material is generally the same size as 5/4 lumber (or close to it).

Pro-Tip: Overhead power lines must have at least 10′ of clearance. These lines will later be buried to meet that requirement.

The crew got all the joists set in place and secured with joist hangers, including a double-joist in the middle. Since the deck was 24′ long, the band board consisted of two 2 x 8″s butted against each other, and the transition at the double joist.

Using a string guide, the guys marked the ends of each joist and cut away the excess with a circular saw.

The band board was situated between the rim joists and secured with four nails per joist. Note that the last joist was 1.5″ longer to remain flush with the band board. This allowed nailing from the side of the joist into the board.

Pro-Talk: A rim joist, or band board, is the final joist that caps the end of the row of joists that support a floor.

Blocking in between the joists provided a surface to mount the rail system. This was especially important because they planned to “picture frame” the perimeter to conceal the cut ends of the composite deck boards. To achieve this, the crew cut pieces of 2 x 4″ to fit in between joists and sistered a 2 x 4″ along each rim joist.

Building the stairs was not an overly difficult process; the key to success was making accurate cuts. In this short video, Steve shares how he calculated the stair stringer dimensions.

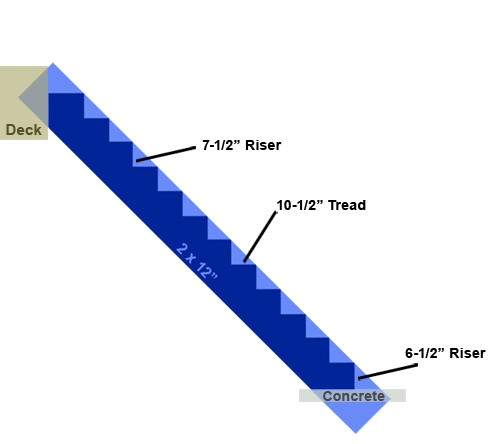

Video Summary: Steve describes how he started the process to build the stairs by first determining the total height of the stairs. Stair risers need to be between 7 and 7-3/4″ tall, and using 7-1/2″ translates into 12 risers. Likewise, stair treads need to be between 10 and 11-1/4″ wide. Since they will have 12 steps, the tread needs to be 10-1/2″ with a 3/4″ overhang. If this still seems confusing, Todd from Home Construction Improvement has a very simple Stair Stringer Calculator spreadsheet you can download for free.

With the rise and run dimensions calculated, it was time to mark the stringer. Watch this short video for more information about marking the 2 x 12″.

Video Summary: This video shows how to scribe the stair stringers. It’s important to check the crown of the board and make sure it’s “crown up.” Using a framing square, line up the rise and run measurements on the edge of the stringer and mark your line. Then you move down and repeat the process. Lastly, extend the first line (riser) through the 2 x 12″ and cut off the excess.

I put together these diagrams to help visualize the stringers. You’ll notice that the very last step is 1″ shorter. That’s because there are no deck boards on the concrete, and shortening that riser keeps each step height consistent.

The stairs measured 4′ across and to maintain the 12″ oc supports they will needed a total of five stringers.

The two outside stringers were slightly longer so that the cross member was situated in-between them. The inside stringers butted up against the cross-member, and this was important because it allowed Steve’s crew to drive nails in two dimensions for a more secure hold.

These pictures show how the guys assembled the stairs.

In the diagram above you see mention of a concrete pad. It’s important to have something solid at the bottom so the stairs don’t just sit on the ground which will erode over time. While building the stairs, the guys also built a concrete form and poured a small concrete pad.

This pad had two “footers” where the stair rail posts will be situated.

Here are a couple of shots showing the stair landing. It measured approximately 4 x 4′, and the joists and band board were installed just like the rest of the deck.

After the concrete cured, they moved the stairs into place with the top of the stairs resting on the deck support beam.

Steve’s crew checked that the stringers were level and then nailed them in place.

Contractors use flashing to prevent water and moisture from finding their way into a home. The general idea is that since water flows down with gravity, you can overlap waterproof membranes (like siding, stucco, metal flashing etc.) that will direct water away from the house. Improperly flashed decks can cause a lot of problems, because leaks may not be visible right away, and they are not always readily diagnosed. Furthermore, making repairs after a deck is finished can be a very onerous task. (Although some deck construction methods make it easier to address such challenges than others. We talk about that below.)

The Unique Situation with this Deck: The exterior of the house is a combination of brick and block. The ledger board was fastened to the brick, which is already constantly exchanging moisture with the outside world. Since the masonry anchors Steve used did not penetrate deep enough into the brick to disrupt the moisture barrier, Steve’s crew was confident that this deck did not require separate flashing. (There is no path for water to enter the home.) Typically, the crew would err on the safe side and flash anyway; however, in this installation flashing would have been visible and would have detracted from the look of the finished product.

This situation with this deck is unique because the ledger board in this design was not a load bearing element. This deck is freestanding, with two sets of posts and beams on which the joists sit. In most decks, the ledger board is load bearing, and the bolts go all the way through the rim joist of the house. This situation always requires flashing to prevent leaks, and it’s recommended that holes drilled for bolts should be filled with a silicone sealant. Look for helpful links including 2012 International Building Code (IBC) and International Residential Code (IRC) in our Related Content section at the end of the post.

If the crew had decided to flash the deck, here’s how they would have done it:

Pro-Tip: Newer chemicals for pressure treated wood like alkaline copper quaternary (ACQ) and copper azole, are more corrosive, and aluminum flashing and steel z flashing actually deteriorate when in constant contact. For that reason, use a rubber or copper flashing product. One reader also suggests using 1.5″ wide strips of #15 building paper between the two can also prevent problems.

Step 9: Lay the Composite Deck Boards

Steve’s crew installed Trex Transcend composite decking boards for this build. The homeowners were really excited about this, because composite decking is almost completely maintenance free. They won’t ever have to worry about sealing, stripping or brightening the boards. The band board and stair risers will be wrapped in a white, Trex composite trim.

Trex is a capped-stock, which means the core of the board is composed of a different material. For that reason, exposed ends are especially undesirable, and Steve’s crew created a “picture frame” around the perimeter to conceal the board ends.

The guys knew that the house wall was not 100% straight so they ripped the first piece of Trex in such a way as to eliminate as much inconsistency as possible.

They cut a 22.5° scarf joint to conceal the transition from one board to the next.

Pro-Talk: A scarf joint is made by overlapping two pieces of wood along a tapered, beveled, or chamfered end.

Steve’s crew used screws designed for composite decking. If you look closely, you’ll notice that the top is reverse threaded which holds the screw in place while the screw-head acts as more of a plug.

Screwing down the deck boards was slow going because each screw needed to be pre-drilled to prevent the board from becoming disfigured. Besides the added cost of materials themselves, this step made the installation of composite decking more expensive than the installation of traditional pressure treated products.

After the guys set two adjacent pieces of the “picture frame” in place, they started laying the diagonal boards. It was important that the first board be laid accurately, because they acted as a point of reference for all of the others.

Steve’s crew cuts the end at a 45° and measured the opposite side to ensure the angle stays true.

Each board was secured with two screws at every joist.

Pro-Tip: You can opt for hidden fasteners that are driven into the side (rather than the face) of the deck boards. This requires a specialized jig and incurs some extra cost.

All decking (composite and traditional) will expand and contract with changes in weather, and it’s important to adequately space each board to provide that necessary room. To achieve a uniform spacing, Steve’s crew sets up a block with 8d nails to create the gap.

This picture shows the progress after a few rows have been laid.

Pro-Tip: Trex composite features a wood-grain inlay to make the boards look more like a natural product. The wood grain is a pattern that you’ll see repeated many times over the length of a single board, and if you’re not careful to stagger the pattern, it will be readily apparent to anyone looking at the deck.

After the diagonal boards were in place, these ends were trimmed with a circular saw.

Pro-Tip: Even though I describe this as a 12 x 24′ deck, it will actually measure a few inches shy of 12′. If the homeowners had truly wanted a 12′ deck, it would require Steve to purchase 20′ composite boards since they’re being installed diagonally, and that jumps the price up significantly. By making the deck just a little shorter, Steve can purchase 16′ composite boards and provide a more cost-effective solution.

Here are some images that show how the deck progressed.

They snapped a chalk to mark their line for the circular saw.

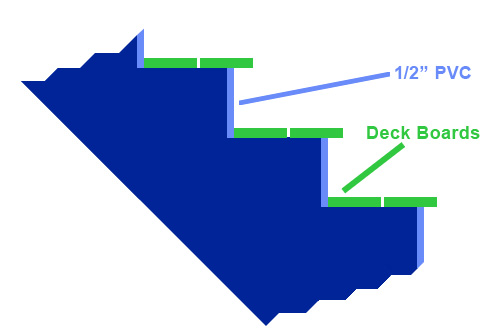

Steve’s crew installed a white, 2 x 12″ PVC trim board on the outside stair stringers and the band board. It gave the deck a nice, polished look and matched the rail system. PVC is nice to work with because it’s lightweight, flexible and maintenance free. The guys mitered all the corners and used finish nails to fasten the boards.

They filled all the nail holes with a PVC putty so that you can’t even see the nail hole.

To cut the PVC to match the stair stringers, they cut the very first riser and temporarily tacked the PVC against the stringer for marking cut lines. This was better than re-drawing the stringers because even the most accurate carpenter may have some variation, and this ensured that each section matched perfectly.

Editors Note: We are walking through this deck build chronologically, but stair stringer trim is best left after the treads, risers and stair guards have been installed.

PVC is easy to cut, so a jigsaw makes short work of cutting out the stringer trim.

After getting the trim in place, the guys moved onto the stair treads and risers. Every three or four steps, they added blocking to ensure a consistent width.

Steve’s crew also added these blocks at the base, which will have concrete anchors driven into the small slab below. The two outside bays don’t have blocks because they’ll have stair posts (eventually).

Starting at the top, the crew measured the riser first, cutting a piece of PVC long enough to reach across the cut edges of the stringer trim.

Next, the crew cut the first tread. You can see how that the tread does not extend the entire length. This is on purpose, because the crew left room for a return piece to conceal the cut edges of the tread.

This picture shows one of the return pieces that hasn’t been fasten yet. It was slow going to get all the cuts exactly right. To help themselves out, the guys put together templates. The return pieces were secured with screws through the side of the return and into the tread board.

Another small detail that you might have missed is that the guys notched out the stair riser for the return piece using a Bosch multi-tool. This notching makes the tread appear to go under the riser when viewed from the side, which creates a nice visual look on the staircase.

Steve’s crew installed a white, vinyl rail system, and the picture below shows one of the steel posts and plastic spacers.

Remember the blocking between joists around the perimeter of the deck? That blocking allowed Steve’s crew to securely fasten the steel posts with 3-5/8″ LedgerLOKs. Each post was leveled as necessary with shims, ensuring it was perfectly vertical before fastening. After the LedgerLOKs were installed, each post got a plastic spacer which serves as a guide for the PVC trim cover.

Pro-Tip: The International Residential Code (IRC) requires rails to resist a load of 200 pounds.

Next, the guys trimmed the vinyl sleeve to the appropriate height and slipped it in place with another plastic spacer at the top. They placed posts about every 6′.

Pro-Tip: Deck railings are required to be at least 36″ tall.

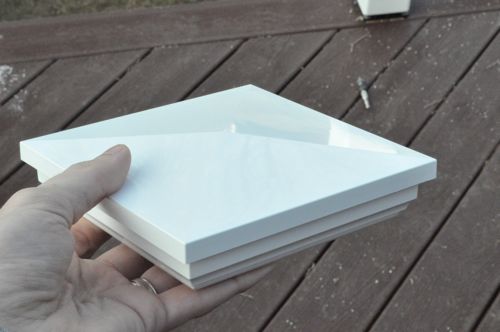

Here’s a picture of one of the post caps. These were installed last and are usually glued in place to avoid using fasteners.

After the posts were set, the guys slid a square, base trim piece over the vinyl sleeve to conceal the bottom of the steel post. Next, they cut the lower rail to length and screwed it in place. It’s important to cut an equal amount from both sides of the rails to maintain a balanced appearance for the pickets.

Pro-Tip: The lower rail should be low enough that a 4″ sphere cannot fit underneath the rail.

This rail system had convenient mounting brackets for the upper and lower rails which included plugs and caps to conceal the screw heads. After the lower rail was fastened, they inserted a picket into each hole.

The upper rail was installed in a similar fashion, except for one additional step. The upper rail had an aluminum channel for increased strength, and Steve’s crew needed to trim this channel to length.

The guys placed 4 x 4″ pressure treated posts at the bottom and middle of the stairs. The set at the bottom rested on the concrete pad and were through-bolted in place.

The middle set ran all the way into the ground where they were secured much like the deck posts: a 30″ deep hole, concrete footer, and backfilled with dirt. They also through-bolted these and had to notch the stair treads.

Each post was cut at 36″ and a vinyl sleeve was fit overtop.

The stair kit had angled brackets. However, the guys needed to cut the hole for the picket.

Steve’s crew cut the upper and lower rails at a 35° angle, and trimmed them to length with equal portions cut from both sides to maintain an even appearance. The holes on the upper and lower rails were slightly bigger to allow the pickets to stand plumb.

Code requires a continuous handrail so they added this metal-core rail on the right side to meet that need.

Here are several pictures of the finished product. This deck looks fantastic, and will be excellent for entertaining and enjoying the outdoors.

Special thanks to readers Jeff Williams, Icarus, Haus356, William, MissFixIt, Joe, Jake, Eek565, JD, Reuben Collins, Simon, and John. Without great questions and comments, this how-to wouldn’t be nearly as complete.